Targeting Cervical Cancer in Cajamarca, Peru: Initial Study Insights, Surprises, and Next Steps

- Nov 15, 2022

- 5 min read

If you have been following the work of GWHT for the last several months, you may know that we launched a long-awaited study with Dr. Patricia Garcia and her team earlier this year to implement a new model for cervical cancer screening and treatment using low-cost technologies aiming for improving the continuum of care for women in Peru. You can read our introduction to this study here.

Now several months into the study, we spoke with Libby Dotson, GWHT’s Research and Development Engineer, about its progress and some initial findings from this exciting and compelling research.

What is your role with the current study GWHT is conducting in Peru?

My name is Libby Dotson and my work focuses on bridging the gap between engineering of medical devices and the implementation/adaption of those devices into unique contexts. I support Dr Nimmi Ramanujam and Dr Patricia (Patty) Garcia in the management of the study in terms of device readiness/functionality, clinical workflows, funding management, and management of reports to funders and government officials.

How many people have been enrolled in this study? Who is eligible for enrollment?

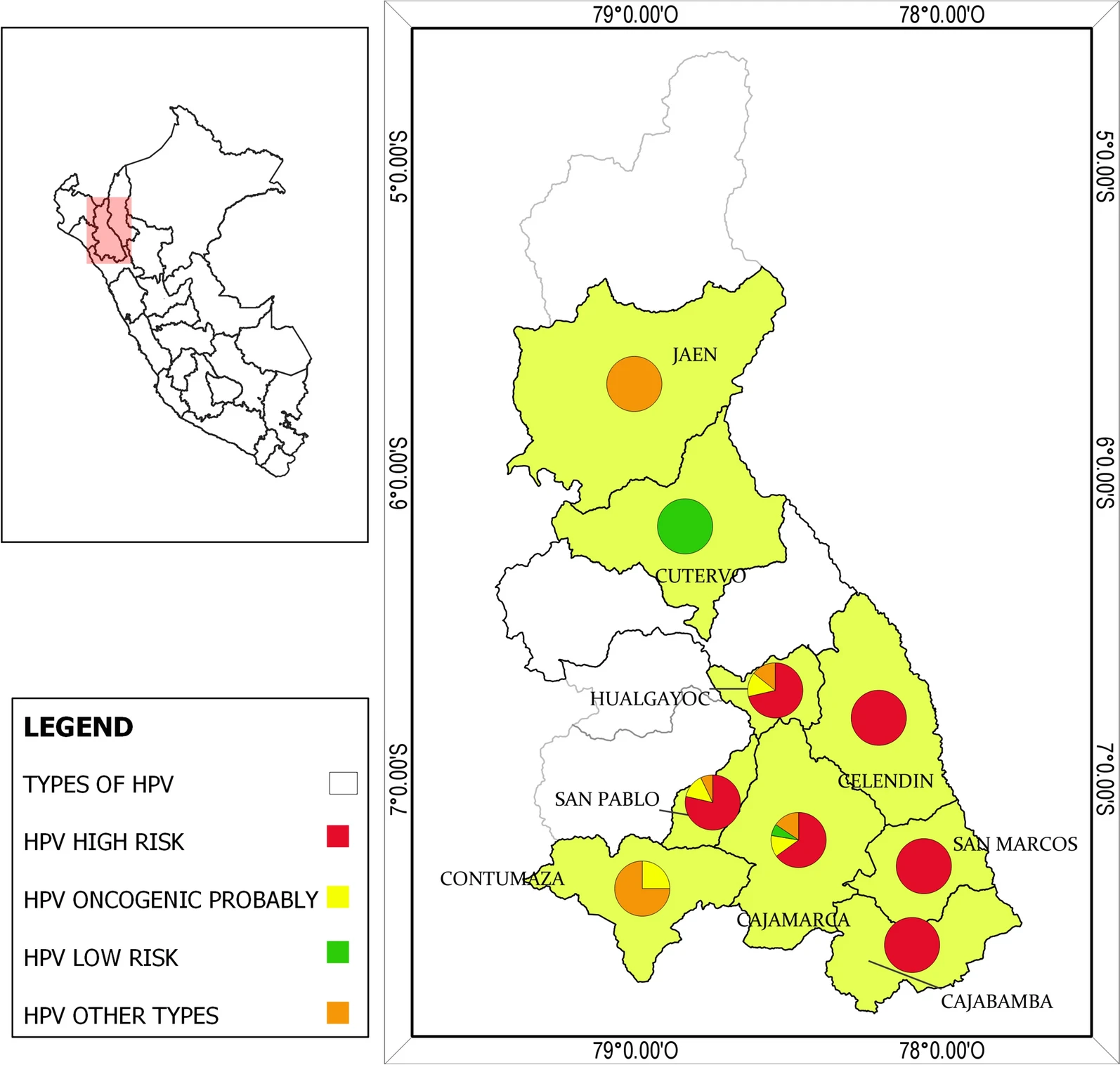

Almost 4,000 women have been screened for HPV through the collection of their own sample after training by community health workers. (You can read more here about the HOPE project in Peru, which has a strong focus on making HPV self-sampling more accessible for the general population).

Around 18% of these women tested positive for HPV and all were referred to a primary health center for follow-up diagnosis with Pocket Colposcopy. Almost all women (around 92%) were treated for thermal ablation at the same visit at the health center. (For reference, this rate is much higher than the prevalence of HPV in the rest of Peru, and certainly more prevalent than in higher-income countries like the U.S.) The small subset of HPV-positive women with more advanced lesions or lesions that couldn't be managed with thermal ablation were referred to second- or third-level hospitals for treatment.

You can click through the thumbnails of the slides below to follow the care pathway that Libby Dotson describes in our conversation

What are the goals of this study in particular?

The objective of this study was to evaluate a new care model for cervical cancer screening and treatment in an under-resourced Andean community called Cajamarca in Peru. One of our goals is to understand how this new model or implementation strategy could improve screening and follow-up rates without increasing the cost of care to either the individual or the healthcare system.

A secondary goal was to evaluate the use of the Pocket colposcope as a tool for primary care health providers (in our case professional midwives) to use ‘tele enhanced visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA)’ whereby midwives take cervical images, then send those images along with a medical health record to a HIPAA compliant database. An OB-GYN reviews the images remotely to assign a diagnosis, then communicates that diagnosis and treatment plan back to the midwife who then works with the patient to either treat them during the same visit or schedule a follow-up at a higher level health center or hospital as needed.

What has your team learned so far?

We have learned that using the Pocket colposcope is a more effective alternative to standard VIA for cervical cancer screening, and that midwife-enabled “tele enhanced VIA” is not only feasible but preferable in many clinics. With this system we can offer diagnosis and management at the same visit reducing the risk of need for follow up. We have started to create better and faster operational processes to implement our package of technologies.

Specifically, we have improved our image capture, storage and mobile app to enable effective linkage between the primary health care clinics and the second and third level hospital such that there is a continuum of care for each patient. Further, we have found that documentation of each procedure along with images at each touchpoint enables all providers to know the history and status of each woman and helps to review cases and improve the learning experience of the providers and the management of the patients. This is just one example of how technology and feedback on the ground has influenced the care pathway.

Clinic space at a primary health center in Cajamarca, where HPV(+) women are examined and treated.

The pocket colposcope and the thermoablation devices can be seen on the table.

What has challenged or surprised you?

While both midwives and providers were on board with evaluating this new implementation strategy, our team encountered several logistic/operational challenges within the clinics themselves. For example, the clinics did not have adequate lighting, so we bought midwives each a headlamp. Further, the size of the gynecological exam tables, including the placement of the stirrups for feet elevation, is incorrect for the standard height/weight of the women in this community. This has actually spurred several design projects, one being the actual comfort and positioning of the patient for a gynecology exam.

We have also received incredibly helpful feedback from healthcare workers in the field that has influenced our work, creating a reciprocal cycle of learning and development.

What has been meaningful about this work you have been doing?

The most meaningful part has been watching the midwives become more empowered to do a better job in the diagnosis and treatment of women through the imaging of cervices with the Pocket colposcope.

The Pocket allows midwives to improve their clinical workflow with a highly effective technology that not only provides visualization of the cervix to examine lesions, but also captures images for medical records. This shift empowers midwives to provide a higher level of care than visual inspection with the aid of flashlight alone, and to be able to discuss the cases virtually with the experts and improve their learning.

How have things changed with this project since 2020, when you were meant to begin (before COVID)?

We were meant to start enrollment in March of 2020, enrollment was delayed by 2 full years. During this time additionally to all the issues related to the pandemic, there was a lot of political unrest and government elected official turnover in Peru. We found ourselves having to redesign the project over the course of the 2 years in lockdown and continuously work to obtain new approvals when there was turnover in the national and regional healthcare systems.

What are the next steps?

The next steps are to analyze the massive amounts of clinical and costing data we have collected and present the results to the regional and national ministries of health in Peru. Our goal is to obtain governmental buy-in to this alternative implementation strategy so that it is subsidized after study completion.

Some of the members of the Peruvian Team from Left to right : Dr. Patty Garcia, Melita Reategui (Community Health agent), Marina Chiappe (Laboratory coordinator), Maria Valderrama (Field work coordinator)

Comments